When You Should—and Shouldn’t—Teach for Free

Ever feel the exciting rush of landing your first gig, only to have your stomach drop when you realize you won’t be paid?

If you haven’t found yourself in this tricky situation yet, you might’ve still heard the warning stories from other dancers. And if it’s one of your first serious offers to teach or assist, it can be tough to know what to do at that moment. But stressful as it might feel, there are plenty of ways to decide whether working for free is something you should do. It will almost always be different depending on the job, and there’s no right or wrong answer—what matters is you do what’s best for you.

Figure In Your Finances

Every dancer’s financial situation is different. Before you go exerting your time and creative energy for free, you should ask yourself: “Can I afford to do this?” You might have a solid financial support system at home, and a bit of free time to make that unpaid work possible and worthwhile. But if dance is something you pay for on your own, then it’s worth crunching the numbers to see if giving away those precious hours is something that could ultimately set you back on your road to success.

“Of course, when you get asked to do a job, initially it’s so validating. But know that you can’t do everything,” says Jessica Chen, founder and artistic director of J CHEN PROJECT modern dance company in NYC, who also heads up her company’s congruent mentorship program for young dancers looking to go pro.

If you’re worried about the money, but it’s a job that you genuinely think you’d enjoy and could really help your future (we’ll get to that), it’s worth being transparent from the beginning. “If you end up in a situation where the booker or theater doesn’t have funds to pay your whole fee, then it’s important you set boundaries and discuss reasonable expectations for the project,” Chen shares from experience. If you communicate that you are very invested in and inspired by a project, the other party may be willing to make additional accommodations.

If a potential boss doesn’t seem keen on (or kind about) discussing any of your concerns, this could be a red flag that these might not be people you want to lend much of your energy. (Especially if you have an inkling that they’re big enough to have a budget to hire you for pay.)

Jessica Chen

Photo by Paul Dimalanta, Courtesy Chen

Consider More Than Money

Sometimes, you can be paid for opportunities in other ways that aren’t cash, and that’s perfectly OK as long as you’re comfortable with it. This might look like someone offering you free rehearsal space in exchange for your time. Or maybe the reward you get out of a job is simply learning the ropes from a seasoned pro you admire.

“Sometimes it’s nice to assist because you don’t have the pressure of being the lead person, teacher, or choreographer. It’s nice to be able to experience somebody else’s teaching style,” Chen says. “You can learn from and experience the process in a no-pressure manner, and explore your own teaching and choreographic methods.”

Plus, if it’s a style of dance you’re hoping to sharpen, being an assistant or demonstrator for someone can be a pretty peachy deal, because while you might be technically working, you’re still getting to take class for free and continue to hone your skills at the same time.

Megan Bowen

, CEO/founder of Dance From Home, LLC, and a popular social media dance guru known for her TikToks that pull back the curtain on the realities of the industry, says to think of it like you’re getting paid the $20 an hour that you’d spend to take a class. “That’s a great example of an equal exchange of energy, if you’re not actually getting a check written,” Bowen says.

Megan Bowen

Photo by Jordan Eagle Photography, Courtesy Bowen

Start Setting Your Standards

Beyond those assisting jobs, Bowen doesn’t usually suggest accepting unpaid work, unless it’s seriously something that fills your cup or will take your career to the next level.

“You have to learn how to value yourself. If you never set those standards for what you do, then you’re never going to make money. And you have to start right away,” Bowen says. It’s the same reason she’s always adamant about paying the artists she works with the best rates she can. “I know the work that I do and the ‘Megan’ that I bring to the table is so much better when I’m being paid for my time.”

If you’re still feeling torn, Bowen and Chen both offer the same tip for finding your answer. Ask yourself: Does this job align with you? Additionally, Chen asks, is this person who you are potentially assisting somebody you’d authentically want to support?

Chen suggests taking some quiet time, thinking on the opportunity and, most importantly, staying true to yourself the whole way. You should think about all that you might be able to learn from the experience.

“One of the things that I ask my mentees to think about is: What are the three dance experiences you want?,” she says. Whether that’s dancing on Broadway, dancing on TV, touring repertoire with a company and so on, whatever your visions for your career might be, Chen says, “work backwards from there. Then when an opportunity presents itself, that’s something to consider.”

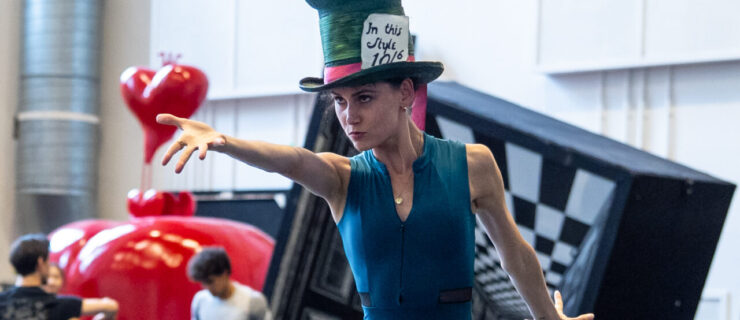

Jessica Chen (left) in class

Photo by Melissa Bartucci, Courtesy Chen

Trust Your Gut

At the end of the day, know that it’s OK to say yes, and it’s also OK to say no.

“Being an artist is expensive; taking class and keeping up with your training is expensive,” Bowen says. As someone who grew up without financial support for her dance dreams, Bowen says she began to notice how easily dancers can get shamed for doing outside jobs instead of dedicating every hour of their day to dance. “But that’s a privilege,” she says.

Instead, what helped her find her own path to becoming a professional was realizing how useless it was to compare her own journey to that of other dancers, and that you can’t be afraid to do whatever it is you need to do to make your creative passion possible.

“You have to just laser focus on what you do have, and what your skills are,” she says. “Young dancers need to know that you’re allowed to make money, you’re allowed to thrive, you’re allowed to be financially secure, and if that requires other sources [of income] to do so, then that’s totally fine. It does not make you any less of an artist.”