Pirouette Troubleshooting

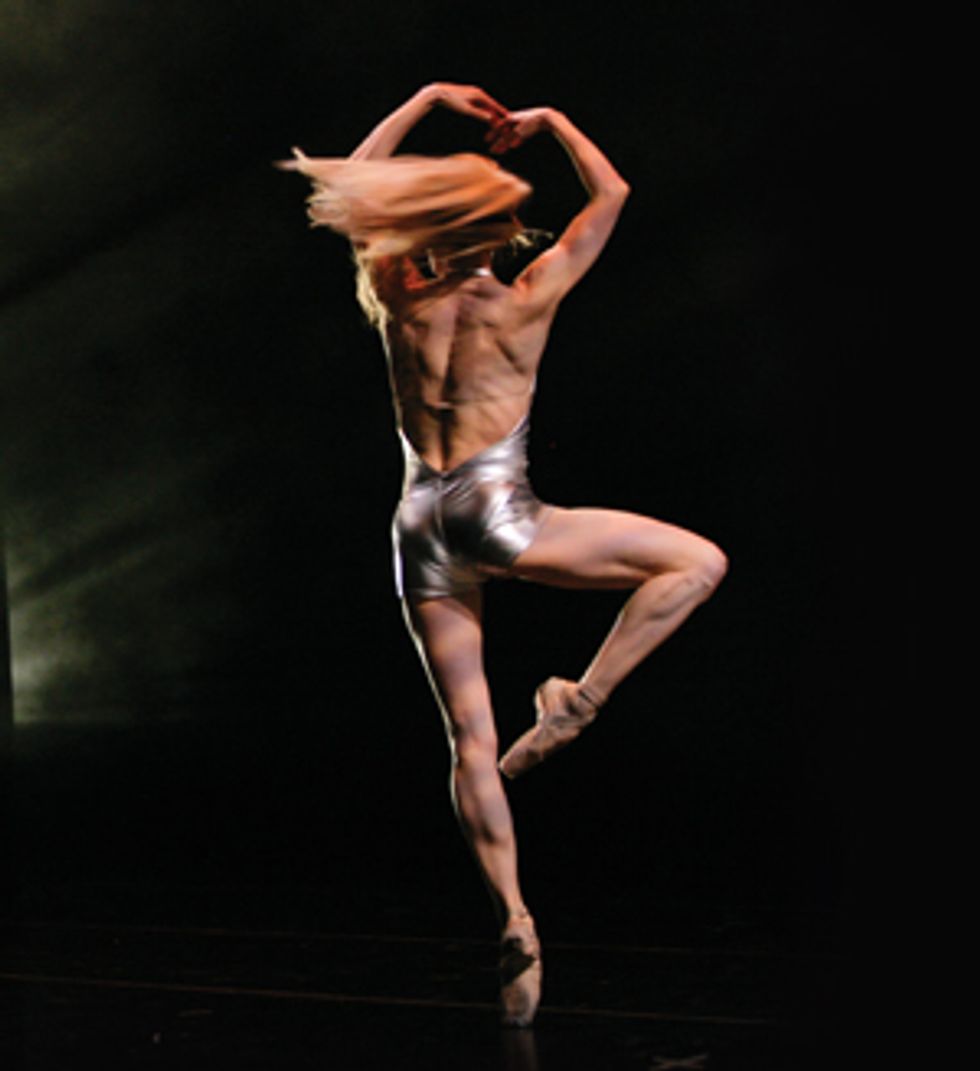

Christine Winkler mid-pirouette in Darrell Grand Moultrie’s Boiling Point (by C. McCullers)

Ah, pirouettes. They’re delicate little operations. Nothing beats the rush of finishing a set of solid multiples, but even the smallest mistake can keep you from nailing that triple. With many variables to think about—placement! timing! spotting!—it’s easy to feel frustrated when you’re tackling tricky turns. DS spoke with a team of pros to help you identify and fix common pirouette mishaps.

Help! I can’t get it all coordinated!

If your pirouette feels like a washing machine spin cycle, chances are you’re suffering from a lack of coordination. Roberto Muñoz, ballet program director of the Colorado Ballet Academy, often sees dancers anticipate pirouettes en dehors by turning in the supporting foot before even taking off. That causes them to open their working hip and shoulder as they continue around, dragging their port de bras behind. “Their arms never catch up with their hips,” he says.

Instead, try to arrive at your passé position immediately by simultaneously springing to relevé and bringing the arms in to first. Focus on keeping the supporting leg turned out, and initiate the turn by pushing off the back toes. Hold your core in one piece—from shoulders to hips—and think of your arms as the steering wheel guiding it around.

To feel the connection of your shoulder to your ribs and hip on the supporting side, Atlanta Ballet dancer Christine Winkler recommends practicing single pirouettes from fifth position en face (landing fifth back), since that preparation is more compact than the preparation for pirouettes from fourth. “You feel like you’re pulling in rather than going around,” she says.

Help! I can’t spot!

An indecisive, lethargic or overeager spot can easily throw off your pirouettes. First and foremost, determine where you’re spotting before you turn—changing mid-turn is a recipe for disaster. Pick a specific object or point in the room to return your eyes to each time. “Your focus is so important,” Winkler says. “Know what you’re looking at and commit to it.”

Some dancers disrupt the momentum of their pirouettes by spotting too slowly, whereas others whip their heads around with too much force. Bo Spassoff and Stephanie Wolf Spassoff, directors of The Rock School in Philadelphia, tell their students to pay attention to the musical rhythm of the spot, and to think of each rotation as a pearl on a necklace. “The necklace is a whole made up of distinct, individual pearls,” says Wolf Spassoff. “Likewise, each pirouette should have a clear identity, defined by the spot—one, one, one—so you get the full picture of each turn.”

The Rock School’s Rachel Richardson prepares for a pirouette. (by Tiffany Yoon/courtesy The Rock School)

Help! I can’t keep my balance!

Whether you tend to lift your working hip, sit in your supporting side, or throw your upper body back, poor alignment will surely knock you off balance. “Body alignment and strength are key to turning successfully,” Spassoff says.

“It’s not enough to think ‘pull up,’ ” he continues. “What does pulling up mean?” Of course, square hips and shoulders, rock-solid abdominals and a strong supporting leg are vital. But he also recommends analyzing pirouettes from a physics perspective. What forces are necessary to maintain your balance?

To stay on your leg, think of opposing energies going up and down as you relevé, like a bow and arrow. “Push down into the supporting foot while at the same time lifting the passé foot,” Spassoff says. As you press down, think of growing taller to avoid sitting in your hip. “A lot of dancers never reach the full height of their pirouette,” Wolf Spassoff says. “If someone came and poked them in the supporting side of their derrière, they’d grow two inches!”

Help! I can’t turn on pointe!

Pirouettes on pointe create a whole new set of problems. For one thing, that tiny platform means less surface area and a lot less traction. “You don’t need as much force on pointe as you do in slippers,” Muñoz says, “so you have to adjust accordingly.” Winkler recalls pulling in from 32 fouettés with extra punch during a performance, hoping to finish with multiple pirouettes. She ended up on the floor, sitting and spinning in her tutu. “I was doing some sort of breakdancing thing,” she remembers, laughing. “I used too much force, and it wasn’t timed correctly.”

Many dancers approach pirouettes from pointe more tentatively and

consequently arrive in passé too late. “You immediately have to get to the

full height of your passé,” says Wolf Spassoff. In addition, try not to give in to the clunkiness of the pointe shoe box. “Think of a quick, light toe coming right under the center of the body, and pull up and out of the shoe.”