Seeking Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in Competitions and Conventions

The world of competition and convention dance has always had its share of supporters and naysayers, folks who laud the circuit for providing up-and-coming dancers opportunities to perform, and others who argue that the comp/con world encourages tricks and acrobatics above artistry. But amidst these important conversations, one question rarely gets its due coverage: Are those at the forefront of competition dance—competition owners, convention staff and studio directors—doing enough to diversify the space?

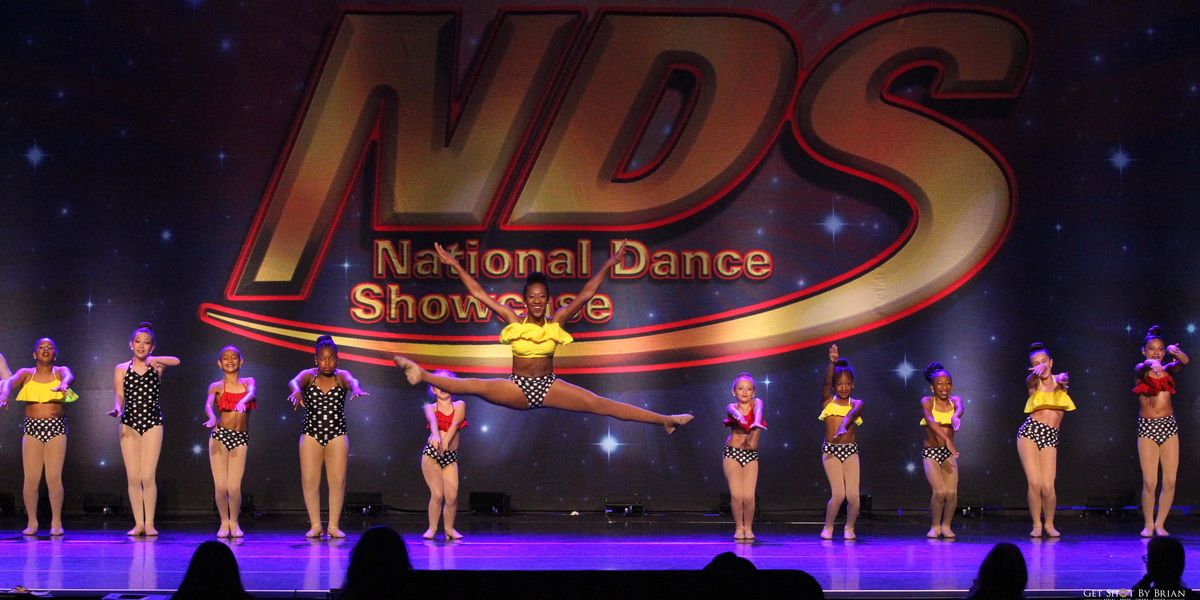

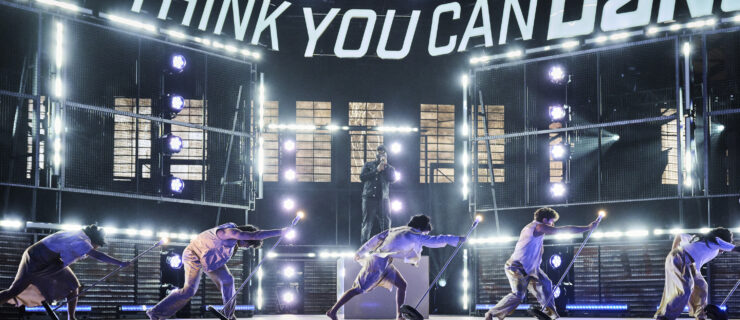

To arrive closer to an answer, and to get a better sense of the community’s state of diversity and inclusion overall, Dance Spirit spoke with three dance artists who were—or are—part of the comp/con scene: Syncopated Ladies founder Chloe Arnold, who teaches tap classes for New York City Dance Alliance (NYCDA); Jason Williams, who parlayed his years of being a competition dancer into a fruitful professional dance career (you might recognize him from “So You Think You Can Dance,” or dancing with Lady Gaga, or performing at the Academy Awards); and Sonia Pennington, co-founder of National Dance Showcase.

Courtesy NDS

Measuring Diversity and Inclusion

Is the world of competition/convention dance diverse? “No,” Williams answers emphatically. He points to the faculty of several mainstream conventions as an example. “I looked through the websites of conventions I could think of to see how many Black artists they had on faculty,” Williams says. He ran through the list, and he says he found that, on average, “there’s one or two Black teachers on any given convention. So, for the Black students who are there attending, who do they look up to?” One of the exceptions, Arnold claims, is her workplace, NYCDA. “My favorite thing about working for Joe Lanteri is that when there were slim to no other Black women teaching on conventions, Joe made sure to hire me, Martha Nichols, Ava Bernstine and Taja Riley,” she says. “He never steered away from hiring faculty of color, including artists like the late Danny Tidwell, Duncan Cooper and Jared Grimes.”

But exclusivity rears its head in other ways, too, as Pennington explains. “It has been my experience over the last 18 years, as both a competition owner and studio director, that the majority of competitions are not owned, operated or managed by people of color, which inherently affects important aspects of competition, such as the judging panel, as well as the staff working at competitions.”

“The lack of diversity at the top levels of the comp/con world also trickles down to the dancers we see attending these events,” Pennington says. “Dance competitions have historically been marketed and branded in a way that is not always inclusive of nonwhite competitors, in subtle yet extraordinarily significant ways,” she explains, “such as the pictures of the homogenous, white, smiling dancers in most competition marketing materials to the selection of professionals on the judging panel.”

Chloe Arnold

Lee Gumbs, courtesy Kim Hale PR

Moving Forward

To build a more diverse competition and convention world, Williams argues, we have to look at the bigger problem. “The dance world, sadly enough, reflects much of the real world, which is riddled with white supremacy,” he says. “The only difference is that it’s covered in rhinestones and sequins. But the same thing that’s happening out there is happening here.” And, so, the same strategies leaders in larger social activism spaces utilize to create a more equitable society should be implemented in the dance world. For convention teachers who want to see their colleagues look more like the world we live in, for example, Arnold says they should “put pressure on their bosses and suggest wonderful teachers from diverse backgrounds.”

As far as diversifying the student population, Arnold urges competitions and conventions to “do more outreach to have a more diverse student group so that [BIPOC] students know about conventions. Create a new talent pool for the future.”

Pennington suggests that competitions and conventions can support diversity and inclusion efforts “by first acknowledging the culture of dance competitions that has, historically, created such a paradigm,” she says. “Make concerted and sincere efforts to push our industry in another direction by removing practices and patterns that perpetuate a culture of nondiverse participants. Acknowledgment plus action equals real change.”