"Breaking Ballroom" Proves that Everyone Can Cha-Cha

Growing up in the UK, Rashmi Becker loved to dance—but hated the fact that her disabled brother couldn’t participate fully alongside her. So she founded Step Change Studios to address the lack of opportunities for differently-abled dancers to train and perform. In its very first year, the Studios gave over 1,000 people a chance to dance that they may not have had previously. Step Change dancers have performed in community centers and assisted-living homes around the UK, and last year they made their Sadler’s Wells debut with a showcase called Fusion. Now, Becker’s story of opening up the ballroom world is being spotlighted in a documentary short called Breaking Ballroom, which has its US premiere tomorrow night at the Manhattan Film Festival. Dance Spirit spoke to Becker about the future of inclusive ballroom dance, and how you can make your studio a more welcoming environment for different kinds of dancers.

Dance Spirit

: How did the documentary come about?

Rashmi Becker: Last year, I produced the UK’s first-ever inclusive ballroom show at the Sadler’s Wells, a really prominent venue for dance in London. On the back of that, filmmaker Dragana Njegic heard of my work and approached me, wanting to make a short film. She had never come into contact with disabled dancers, so I said to her, “Why don’t you come along to classes, meet our dancers, and get a feel for what it’s about?” She ended up spending four or five months attending the UK’s first-ever blind ballroom program, came to a couple of our performances, and met our dancers. She immersed herself, and the result is a much deeper, more authentic film about dance’s artistic side, but also the value of dance in terms of quality of life.

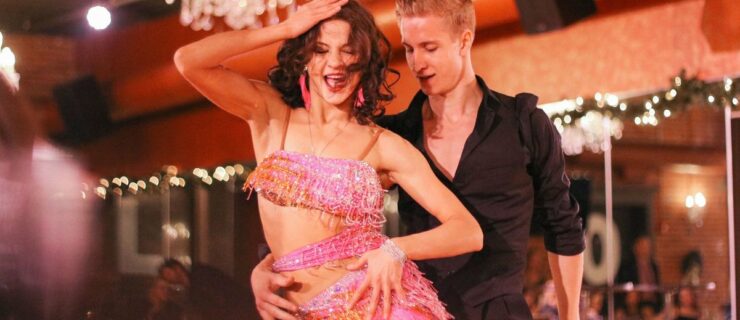

Step Change Dance perform “Fusion” at Sadler’s Wells, London, England in 2018. (Stephen Wright, courtesy Becker)

Step Change Dance perform “Fusion” at Sadler’s Wells, London, England in 2018. (Stephen Wright, courtesy Becker)

DS

: What misconceptions do people have about making dance more inclusive?

RB: There are ignorant comments, like one studio that told me, “Wheelchairs will ruin our dance floors.” Particularly in my genre, Latin dance, people don’t necessarily see the commercial benefits of being more inclusive. And then there are the more cringeworthy prejudices. When Step Change Studios started to grow, taking on more instructors was really difficult. What’s critical as a teacher or choreographer is the creative challenge of being able to adapt what you already know so that people can learn from you. That’s a challenge, whether you’re disabled or not: Everyone learns differently, and it comes down to how you adapt your teaching style. I’ve found it’s about attitude rather than aptitude. I’ve been meeting with dancers, teachers, and schools here in NYC this week, and those are challenges they have as well. What was great about the Sadler’s Wells show was that it was all about the dance. It wasn’t political or wordy or preachy. We had very strong dancers in their own right, and I think that helped challenge dancers’ and audiences’ perceptions. Some non-disabled dancers were dancing in an inclusive way for the first time, so that was a great learning experience for them as well, to realize that the quality of the performance wouldn’t be compromised.

When I produced Fusion, there was a lot of interest from media. Some journalists had very stereotypical views about disability, and asked oversimplified questions like “How do you dance in a wheelchair?” One dancer who used to be a pro but developed multiple sclerosis was asked, “Does it feel not as challenging to dance now that you have to use a wheelchair?” She still trains and works really hard! I was at a contemporary show last night with disabled and non-disabled dancers, and they told me that when they were looking for funding, a potential funder told them that disabled dance “is just not something people are interested in.” But when people see the diversity and quality of the dance, they immediately convert. We have to ask ourselves, What are our preconceptions? What are the barriers we put in place about what a dancer’s body is and who should be able to dance?

DS

: Why ballroom?

RB: In addition to my own more extensive background in ballroom, I feel like the ballroom world in particular tends toward exclusivity. Ballroom and Latin dance has a strong focus on the physical aesthetic. In competitions, it’s about the costumes and the fake tan and amazing nails and makeup and hair. Ballroom hasn’t evolved at the pace of other genres in terms of becoming inclusive. The States are even more active in ballroom than the UK: There are competitions every week, and so many people doing Latin and ballroom around the country. With shows like “Dancing with the Stars,” and the UK’s “Strictly Come Dancing,” the genre is clearly really popular—but the opportunities for interested people with disabilities remain very few. When I was setting up Step Change Studios, I wanted to talk to teachers that were inclusive, and I really struggled to find them in Latin and ballroom.

A Step Change dancer performing “Fusion” at Sadler’s Wells, London, England in 2018. (Stephen Wright, courtesy Becker)

A Step Change dancer performing “Fusion” at Sadler’s Wells, London, England in 2018. (Stephen Wright, courtesy Becker)

DS

: What should dancers know before expanding their horizons to work with a dancer who has a disability?

RB: The biggest challenge is that initial perception barrier of presuming that it’s somehow radically different, that you need special skills. I’ve taught absolute beginner classes where people have no rhythm, can’t count in time, or turn right when you say turn left. When our blind ballroom program had their first exam, it was the examiner’s first time examining people with visual impairment or sight loss. He was really amazed, and said to me afterwards that these beginners had performed better in the exam than sighted beginners. It’s really just about adapting to how people use their bodies to learn in different ways. It’s been shown in business environments that working in an inclusive way produces better results. When you work with a more diverse group of dancers, it makes you more creative and confident, and benefits your artistic intelligence as a non-disabled dancer. Dancers who are training to be teachers themselves have learned from volunteering with us to be a lot more versatile in how they approach dancing and teaching to different learning styles. I’m a visual learner, so I like to watch and copy. Other people I’ve seen carry notebooks in which they write the steps down. I’d love to see performing-arts programs make it mandatory to learn how to work with able-bodied and disabled children and adults. I think that’ll result in a much stronger core of teaching professionals, with much more interesting artistic outcomes as well.

You can catch

Breaking Ballroom on Friday, May 3 at 5 pm at Cinema Village (22 East 12th Street, New York, NY 10003).