What is Downtown Dance?

Imagine this: The curtain rises to reveal a woman standing upstage right, wearing just a white leotard and black high-tops. Another woman, wearing only hot pink shorts and a fake mustache, stands center stage next to a keyboard and drum set. White shiny streamers replace the scrim, and various plastic animals are strewn across the stage. Suddenly, the lights get brighter as someone screams the lyrics to Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal.” The two women start gyrating and thrusting their hips.

Though the scenario may sound like a scene from a new comedy by Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, it’s actually the opening sequence of Snow White, a provocative and stimulating evening-length show by choreographer Ann Liv Young which was performed at NYC’s The Kitchen in 2007. But what on earth do you call such a work? Perhaps the most accurate title would be experimental dance—and while that’s certainly valid, if you’re in NYC, you might also hear it called “downtown dance.”

Essentially, “downtown dance” is a label used in NYC to describe work that is in the lineage of modern dance, comes after the postmodern movement of the 1960s and ’70s, and doesn’t belong to an established technique. Downtown dance historically pushes the boundaries, embraces movement for movement’s sake and is rooted in experimentation and improvisation. These characteristics, however, are elusive, which is one reason why geography—the movement was born south of 14th St in Manhattan—is seen as the most concrete thread uniting the genre’s choreographers.

Pioneers of the postmodern movement like Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay and David Gordon were committed to making work that wasn’t commercially driven, so it stands to reason that they lived and worked where the rent was the cheapest. Believe it or not, in the ’60s, the rent in Manhattan was lowest below 14th St. This economic separation did not exactly go unnoticed. “There was a division between Upper Manhattan and Lower Manhattan in terms of high and low aesthetics,” says Jonah Bokaer, a choreographer and media artist who directs Chez Bushwick, a nonprofit arts organization based in Brooklyn. “Ballet and other more established arts traditions were uptown, while more independent, more adventurous art was happening downtown.”

Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village, which later spawned the Judson Dance Theater, was experimental dance’s incubator. It all started when a group of artists (not only dancers like Trisha Brown, but also composers, writers and painters) participated in a choreography class taught by composer Robert Dunn. Through these interdisciplinary dialogues, the artists developed the idea that dance didn’t have to have a storyline or music; it could be performed in silence or to a mishmash of everyday sounds. The movement could be made up on the spot, be based on pedestrian gesture or depend heavily on props. Basically, dance could go anywhere their imaginations led them.

Controversial Characteristics

NYC-based dance artist Juliette Mapp, whose work is politically charged and incorporates spoken word and comedy, feels that the central characteristic of downtown dance is that it continues to change. “It’s choreography that has an evolving relationship to the body,” she explains. “Downtown dance has come to include a collection of very porous ideas.”

Though she acknowledges its prevalence, Mapp prefers not to use the term herself. “Maybe I shirk a little bit about the idea of downtown dance because I feel like it’s used as a disparaging term,” she says, explaining that experimental art has historically had a rocky reception. “When Cunningham rejected the idea that dance had to in some way have a relationship to music, respond to the music or tell a story, people hated it,” she says. “People,” of course, meaning critics and those entrenched in the more established arts scenes.

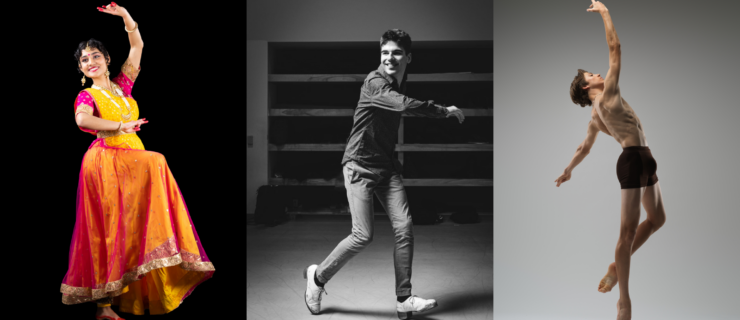

Still, some people love the freedom of the experimental dance scene. Anything goes in this genre. “I think it’s pretty voracious,” says Bokaer. “It tends to include burlesque, cabaret, work that incorporates nudity, work that’s politically charged, and work that slips between dance and theater, as well as installation-based work.” (See “Snapshots of the Scene,” at right, for some specific choreographers’ styles.)

In History

Since Isadora Duncan first flitted around the stage with her flowing scarves in the late 1800s, dancemakers, audience members and critics have added words to our lexicon in an effort to explain what they were seeing and making.

Duncan’s style was called “free dance,” because it broke the constraints of ballet. Then, in the early 1900s, artists like Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey pushed the rebellion even further and created codified movement styles. They were working at the same time as musicians and artists who were also deviating from established traditions and so that label was easy: The entire era across disciplines was called “modern.” But in the mid-1940s, choreographers such as Merce Cunningham and Alwin Nikolais started making work rooted in the idea that any movement is dance and experimenting with notions like chance and the abstract. A new description was needed, and since this was happening directly after and influenced by modern, it was called “postmodern” dance.

Since postmodern’s heyday in the ’60s, there hasn’t been one all-encompassing word to describe the new work made in the lineage of Duncan’s free dance. The label “contemporary” generally means a combination of modern and postmodern elements (and maybe jazz, too!), while other descriptions, such as improvisational dance, dance for the camera and dance technology, are more utilitarian. The NYC-based term “downtown dance” is the only one inspired by where the work was being created—and yet the term is becoming obsolete as the rising price of rental space pushes artists out of Lower Manhattan and into NYC’s outer boroughs. Still, the shift in location is merely a detail, as the type of avant-garde work “downtown dance” has come to refer to is alive and well.

Photo: Steven Schreiber